Article by Claire Sykes

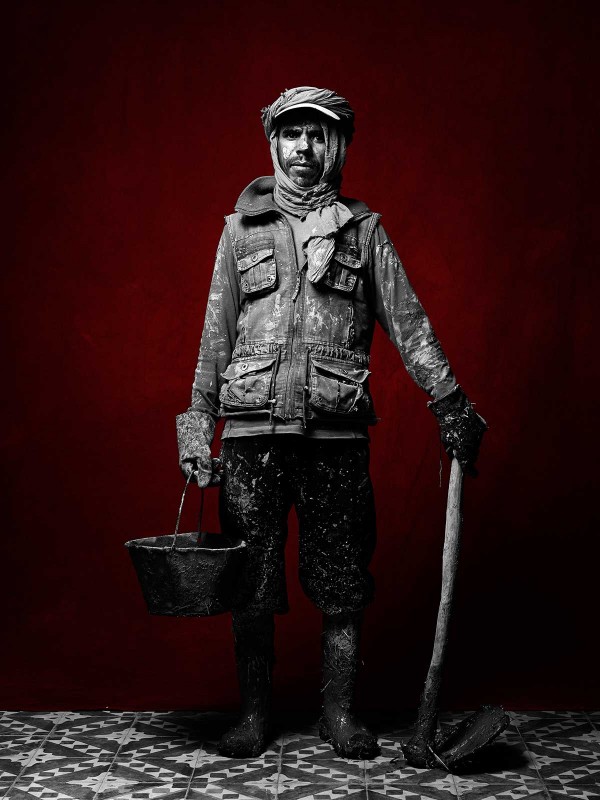

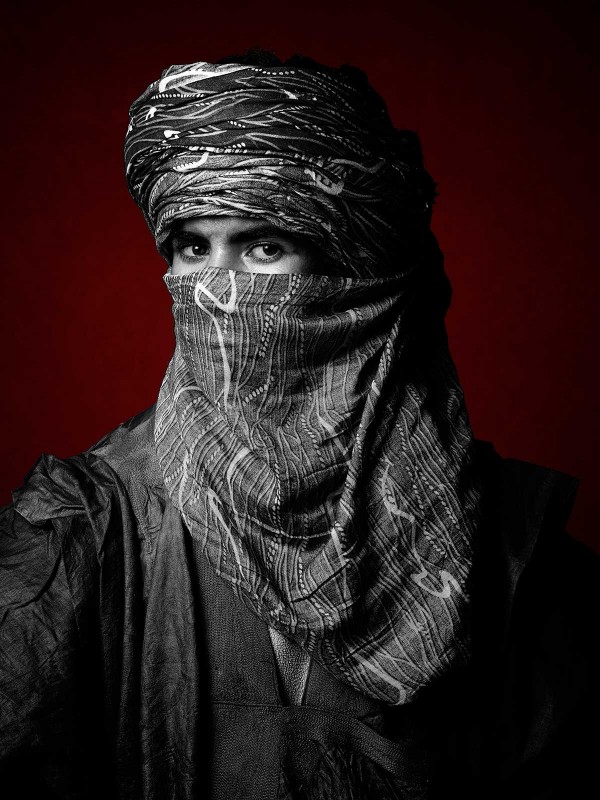

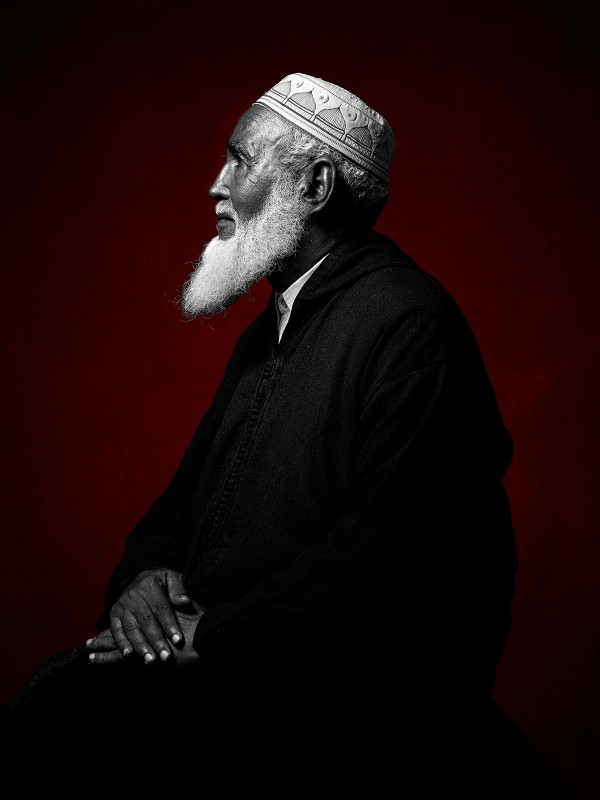

Inspired by Irving Penn and August Sander’s portraits of working men and women, for 20 days in November 2013 Sandro and a small crew traveled around Morocco photographing over 230 tradespeople and children. They went by car, truck, quads and camel from Marrakech to the Atlas Mountains, then to Risssani and the Sahara Desert. Inside rented apartments and riads, mud houses and Moroccan-blanket tents, he fashioned his makeshift, controlled-lighting studios. Here, bakers, Gnawa musicians, nomads, snake charmers, carpenters, mechanics, a fossil-digger and clown stood and sat in front of a deep-red canvas backdrop. Thirty of them, in combination black-and-white-and-color portraits, look out from the pages of Sandro’s self-published Eyes of Morocco (Blanchette Press, 2014), his seventh monograph.

The 12-by-15 ¼-inch hardbound book, designed by Greg Samata, was featured as part of the Chicago Design exhibit at the Chicago Cultural Center, in May 2014. Six months later, Sandro stood onstage at Carnegie Hall before a crowd of thousands holding in his hands the Lucie Foundation’s “International Photographer of the Year Award.” The trophy joins 15 other prestigious awards he has won since 2003, including, multiple times, American Photography’s 200 Best Photographers and Communication Arts’ Photography Annual; and Saatchi & Saatchi Best New Director Award for “Butterflies,” his short video featuring John Malkovich. The 56-year-old Sandro is also recognized as one of the leading advertising photographers in the country, with clients like BMW, Nike and Samsung.

From his Chicago home earlier this month, he talked with me about growing up poor and the power of photography, surviving cancer and the gift of connection, the Moroccans before his camera and the Sahara Desert stars above.

© Sandro

CS: How did you get into photography?

S: I grew up in a very poor family, with no art background at all. My father was killed in an auto accident when I was four and I was raised by my single mom. She was an immigrant from Italy, from a peasant-type upbringing, uneducated and not fluent in English, but she was learning and did the best she could. By my teens, I was really big into sports, but I wasn’t being scouted and wouldn’t have a career in it, and I was trying to stay optimistic in life. There was a tremendous amount of boredom in my childhood and I was looking for a way to escape.

And then I found photography. It was probably a lifesaver for me because I likely would’ve become a wild, distraught, dysfunctional kid otherwise. When I was 16, I picked up a copy of American Photographer magazine, probably because there was a scantily clad woman on the cover. I recall sitting on my bed going through the pages and coming across these portraits by Irving Penn that completely stopped me. One was of Picasso and the other the French novelist and performer, Colette, two images side by side. I didn’t know who Picasso was and certainly not Colette. But because of the lighting and the power of the portraits, I had to find out. It was the power of Penn’s portraits that I knew, that day, that I wanted to photograph people. I wanted to affect others the way those people in the photographs affected me. This was such a wonderful thing for me. Now I had direction for something I wanted to do with my life.

CS: I know you started out as a commercial photographer, shooting product for retailers and catalogs. Then you turned to photographing people—your focus for the last 25 years—at first, friends, people on the street, and Chicago blues musicians such as John Lee Hooker, James Cotton, Buddy Guy and Junior Wells. Among others, you’ve photographed bikers, boxers, a matador and, most recently, John Malkovich, who “reenacts” famous photos in your Malkovich, Malkovich, Malkovich: Homage to Photographic Masters. How did your Eyes of Morocco portrait project come about?

S: I had stage-four throat cancer two and a half years ago. I was trying my best to work every day so the cancer didn’t take over. But I remember days I couldn’t move, lying in my bed, and all I wanted to do was spend more time with my family. But as a photographer, not knowing if I’d be alive in a couple of months, I was thinking, “I want to take another great photograph.” The power of the image is so important to me. I have a collection of close to 800 books, and I spent a lot of time with my photography books. They were my medicine, part of my healing—two books in particular, Irving Penn’s Small Trades and August Sander’s Face of Our Time, documenting people and their occupations. I got inspired by them. I’d always wanted to go to yet another country, looking for something big to shoot. What if I went to Morocco? Use this inspiration from Irving and August and create a different body of work, but with the same story, and let’s make it about street people and their occupations. Wherever I’ve done my projects, I’ve always been inspired by something—a book, play, song, line in a song, book title. And then I thought, “What would make for great imagery?” Whenever I think of any project, it’s got to have a happy ending, an ending that allows people to be interested in this work. Is it going to start a conversation? Is it going to move people? If I can’t get viewers to think or be moved, then I’ve failed.

CS: Why Morocco?

S: I’d been thinking of going to Africa for 15 years, and Morocco is a little bit like “easy Africa.” It’s easy to get a taste of the continent without going straight into the bush. And I really love Black African culture. I love the music, the primitiveness of it, the drums. And it just felt so completely opposite of the big city that I live in. I always thought that Morocco would supply me with amazing stories in the faces of these people.

© Sandro

CS: You photographed Moroccans in black-and-white against an almost imperceptibly dark-red background. Why and how did you bring the two together in a single image?

S: Both Penn and Sander shot in black-and-white, and this project in Morocco needed to have an aspect of that. But I wanted to do something different, like combine color with the image. Done poorly, it looks cheesy, like a gimmick, like someone trying too hard. But I believed there was a way to combine the two and make it into something very special.

Researching Morocco, I learned that it’s known as “Red Morocco,” because of the color of the clay and the dirt and the sand. So I started experimenting with different colors of red. Most of the reds didn’t work, at first. They were too obstructive, vibrant and distracting. Really, the subject is the hero; the emotion you feel from that subject cannot be overpowered by a background. So with more and more experimenting, I found a color I liked in the [Pantone] PMS book, and I bought this huge piece of canvas. We didn’t want to paint the surface of it, because we didn’t want it consistent or even, so we decided to dye it, in a huge tank. And we spent weeks dyeing, experimenting. We’d take it out, look at it, see that it’s too light and put it back into the dye, ten or more times until we got this rich, red-burgundy color. And that’s when I felt that my background of the photo added to the shot and didn’t take away from the subject. All this was done in the studio, and then we brought the canvas background to Morocco.

CS: How else did you prepare for doing this body of work?

S: By doing all my homework here. I spent weeks testing and working with that dark-red background and the lights, and what type of silk to put in front of them. I knew the lenses, the camera format, everything down to the last clamp we had to bring. We had pretty solid notes of how far the background, camera and lights had to be from the subject. I knew I could achieve everything I needed to in Morocco. Of course, we also read about the different types of tribes in Morocco, the Berbers, the people in the Sahara Desert and the Atlas Mountains, the fossil traders [of Erfoud], the snake charmers, bread makers, the spiritual people. I wanted to find people who were different, because they’re more interesting. For me to succeed in a project, viewers have got to want to know more about these people, and why they’re the way they are. I knew I was going to get that.

CS: Who went with you to Morocco and what were their roles? S: I used to work with a Chicago stylist for 20 years, Debby Dean. She moved to Morocco and started a touring company, Nirvana Expedition. Debby and her crew, Houssin Bouchadour and Abdul El Moulou were my liaisons, which is another reason why I decided on Morocco, because I had someone there to help me. She set me up with a driver, an interpreter and places we could stay for the month. I brought my wife, Claude-Aline Nazaire Miller, who speaks French; Moroccans speak French, Berber and Arabic. And I took my first assistant, Aaron Fulnecky.

But from the time we first arrived, in Marrakech, there was nothing but friction. The first four days there the police were trying to get us to not take pictures, and they shut us down. They were suspicious. I knew there’d be some explaining, you know you’ll run into some roadblocks, but I didn’t know it would be so difficult. You get a lot of people taking pictures on the street and then hiding their cameras. When we got to Marrakech, Magnum had sent seven people to take pictures of people in Morocco. They were grabbing shots of them, shoot and run, not thinking about how people felt. It was reportage photographers doing what they needed to do, no disrespect to Magnum. But in Morocco, you don’t do that; it’s an Islamic country. They feel like you’re taking something from them. Magnum left the city with stolen souls. So we were on the heels of all that and it caused us problems. The most difficult was explaining to the police why we wanted to photograph, and my wife did an amazing job. When we finally got the police department on our side, only then could we go out and ask people to come to our studio. I had faith it would happen. I was with a good group of people doing good work, and we had all good intentions to pay people very well to photograph them. I think that’s what helped. After that, there was only acceptance, no resistance, and then it just flowed.

CS: How did you approach your subjects? And how did they receive you?

S: Initially, I was in the streets with Debby, and the two Moroccans she knew who had lived their whole lives in Morocco and knew the areas we could find that little-bit-different person, like the snake charmer. When I photograph, there’s a bit of the Diane Arbus in me, looking for someone who’s not like anybody else. The interpreter walked up to the person, explained what was going on and that the person would be paid 200 dirham. That’s enough money to put bread on the table every day for a year. Throughout Morocco, 90 percent of the people are poor, so we were able to help feed them and their families. We were very respectful to them, and the response was pretty unanimous. Word spread about us. We had a great choice of people, but sometimes a hundred people were coming up to our studio door, and I had to figure out how to say no. It was very difficult, very sad, seeing someone walk off with all this money, and their neighbor saying, “Why didn’t you choose me?” Sometimes I’d give people a little bit of money and say I’m sorry.

© Sandro

CS: How did you decide where you’d set up your portrait studios?

S: The work I enjoy doing the most is in a controlled-lighting situation. No sunlight can be a part of my set. When you’re shooting in Africa and on the move, working out of a truck, you find any place you possibly can where there are no windows—a riad, a small apartment, tents—if the space worked for what we achieved in Chicago. It also had to be central to the people we wanted to bring in, so they didn’t have to walk half a mile; and that it was close to a power source for electricity. Out in the desert we used generators; they were part of our cargo. We ended up shooting in 20 different places on our trip.

CS: What were your days like?

S: We photographed from first thing in the morning until as late as we could. Then we would tear down the studio and pack up all our equipment, and my wife and I worked late at night blogging. We worked 15-20 hours a day. This was the first time for my wife and assistant to take a trip with me, and they now understand the grind. It was a very difficult trip. It wasn’t a pleasure trip; it was about creating work. And plus, it’s my passion. This isn’t about solving a problem for a creative director. It’s about creating work for myself to share with the world.

CS: Aside from the resistance you got from the police in Marrakech, what did you find particularly challenging?

S: One of the hardest things for me there was seeing how women are so oppressed, always covered up and allowing only their eyes to ever see the sun. They were barely allowed to look at me or talk to me. The way I work is all about talking to people, touching their hand, making them feel comfortable in front of me. And now I’m working in a country where I can’t do that. It was very strange, but you understand that this is a different culture.

And I remember this family of snake charmers who came in and they let seven poisonous vipers loose on the ground. They had control of them, but I have a tremendous fear of snakes. This one snake charmer had three of them around his neck and I got within inches to take his portrait. For me, that was like jumping into a pit of snakes. But it’s so important to get the shot. I’m so focused when I’m inside that frame—my eye is moving to every corner of it a thousand miles an hour—that I put my fears aside and I don’t notice anything around me. Even snakes.

CS: In your work, I can’t help but see the rapport with the people you photographed. How did you earn their trust?

S: I think I have the gift of being able to connect with people in a very genuine, pure and loving way. I want anybody who sits for me, whether a celebrity or someone who’s never been photographed before, to have it be an amazing experience. It should never feel awkward or embarrassing. Some of the best experiences are so natural, almost spiritual. And in Morocco, we wanted the experience to be rewarding for the people, not just monetarily. For probably 99 percent of those I photographed, it was their first time in a studio. It made them feel special, enlightened and feeling like they had done something of importance, something that they had never experienced in their lives.

CS: Are there any photos you wish you’d taken?

S: No, I don’t think so. But I could do another 250 portraits, no problem. I don’t think I’m ever done with a project. And my heart tells me I’ll be back to Morocco, especially if the right book deal comes through. I did shoot some beautiful landscapes and more photojournalistic shots, but those weren’t my goal. My goal in Morocco was to shoot very controlled-lighting portraits, Sandro-style.

CS: Why did you decide to self-publish the Eyes of Morocco book?

S: I created it to send to museums, galleries, collectors and book publishers. It was made to showcase the work. The book was designed by Greg Samata and I worked with a printer in Vancouver, British Columbia, Kim Blanchette, who’s printed many pieces for me. He truly understands my work and I knew he’d produce it the way I wanted to show it to the world. Greg, Kim and I are longtime friends; I have found it incredibly important to have friends like these who are at the top of their respective fields. The book is what I sent to the Lucies. If you are going to submit to the Lucie Awards, your work had better be reproduced perfectly.

© Sandro

CS: What does it mean to you to have won?

S: I’ve got to be honest with you. Over the years I’ve won tremendous awards for my work, but winning this one made me cry. I was so moved, being honored, because there were so many great photographers up for the award; I never thought I’d win. When they called my name, I put my hands over my eyes and started to cry! Here we were in such a beautiful venue, with my peers and a few thousand people in the audience, and I was really, really moved by the whole thing. And I think it had to do with coming out of my illness, wanting to create another great body of work and not knowing if I’d get healthy, and then producing this work and being able to go to Morocco—the blood, sweat and hours it all took.

CS: What was most rewarding for you in Morocco?

S: I’ve been to 52 countries, but Morocco is the most amazing. I fell in love with the people and how they lived. And it was truly an enjoyable experience, going out to the desert, riding camels and going to different tents. And just being in the desert. There’s such a beauty in the stars, and you feel you can just reach up and touch them. I was surprised at how moved I felt by the spirituality of it all. I felt very small. All you see is desert and sand, and you begin to feel very insignificant and unimportant, which is a really great thing for all of us to experience. It’s very humbling.

Also, when you come from a country of abundance and go to one like Morocco, you become very grateful for what you have and how you live. That keeps the ego under control. The ego can be an important part of success, but it can get out of hand, and I find that that’s a deterrent to doing great work. When I go to a place like Morocco, I remember where I came from. It’s a completely different country, but it brings me back to my childhood. Back then, I didn’t know I had very little; I felt I had everything I needed, because I had love. We all want the same thing: to provide for our families, and have our children have more than we had. I saw that in Morocco. Whether in the big city or out in the desert with the nomads, I saw the unity of family, the children being loved and having little—but not feeling like they missed anything in their lives.

© 2015 by Claire Sykes. All rights reserved.