By Jamie Ludwig

Andy Goodwin is an award-winning veteran photographer from Chicago whose client roster includes some of the biggest brand names out there including Sony, Vanity Fair, General Motors, John Deere, Aflac and more, but when he found himself with some time between projects just over a year ago, he decided to fill it with some pro bono work rather than his usual commercial fare. The result, a film for Northwestern’s Center on Wrongful Convictions titled, “Exonerated,” brought him personal and creative satisfaction while using his talents to promote a good cause, as well as an award for “Best Picture” out of three hundred entries in the 2016 Midwest Independent Film Festival.

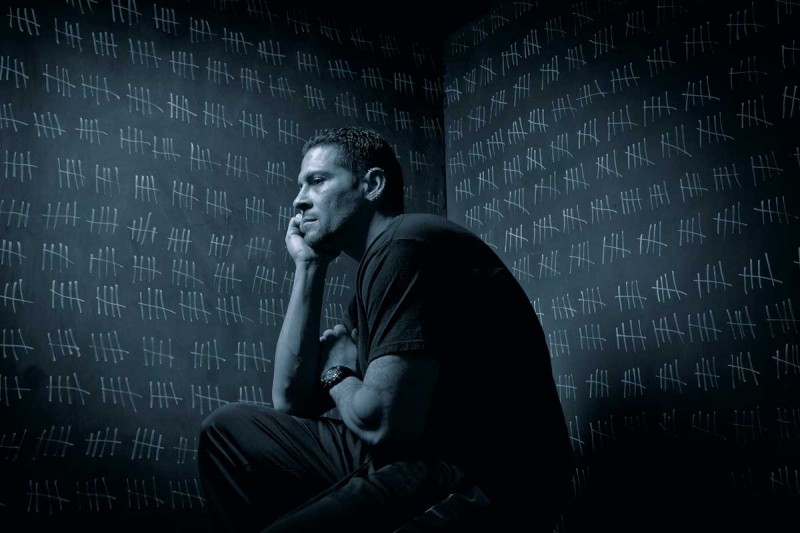

Juan Rivera served 20 years of a life sentence for a crime he did not commit. "Every morning to remind me of where I used to be I go and watch the sunrise so that I can never forget where I came from.” Juan uses the money he received for retribution to help other innocent people reclaim their freedom. Two of the Exonerees featured in the film live with him.

Raised in a family of activists, Goodwin cites the influence of his mother, who launched a foundation that raised money for AIDS research, children’s charities, and other organizations, and his father, who marched with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Selma, Alabama, as part of his inspiration for taking on a charitable project of his own. “This is really my first time in doing anything that even comes close to their efforts but it's just so rewarding and in my opinion—religiously speaking anyway—I feel like God's given everybody a gift and that's maybe what you should use to give back with.”

On a whim, he posted his offer for pro bono projects on his personal Facebook account. In the past he’d used the social media platform to source talent or props for shoots in other cities, but this was the first time he’d reached out for his personal projects. “I’ve got over 2,000 so-called “friends” on Facebook and most of them are in the creative field so I threw out this offer that I had this window and that I was interested in doing some cool pro bono projects. I got a lot of offers, a dozen or so, but by far the most interesting to me was Northwestern's Center on Wrongful Convictions.” The Center, which recently came to greater mainstream attention after being highlighted on the Netflix Original series, Making a Murderer, was launched in 1999 and has since become a leading advocacy and research organization that is committed to challenging and resolving wrongful convictions.

Kristine Bunch served 17 years of a 60 year sentence for 2 crimes she did not commit. "The biggest thing that I would have done with those years is to visit my son's grave and tell him that I miss him. I could have watched my other son grow, learn to ride a bike, go to school and get his first girlfriend.”

Unlike some of the other offers, which included projects like staff portraits for foundation websites, Goodwin saw a unique opportunity to utilize his creativity in a collaboration with the Center on Wrongful Convictions, and after connecting with the Center through a friend, the project began to take shape. They were like, “Here's a list of 25 exonerees, call them up and see which ones you're interested in photographing.” They gave me complete creative freedom and said "Whatever you want to do is fine with us."

Goodwin narrowed his focus to about six men and women living in the Chicago area who had each been in jail for fifteen or more years. Initially, he planned to take environmental portraits of the participants, but after hearing their stories he decided to take the project in an entirely new direction—video. “It became pretty clear early on that we needed to shoot some video too, because the stories were the important part and we needed to hear from them. My wife and I built this background with hash marks on it and made it portable enough that we could lug it around to all six of these homes. I got my son [Jack Goodwin], who's an assistant, and a friend of mine [Lane Cameron] who is a sound guy and DP to graciously donate their time as well.

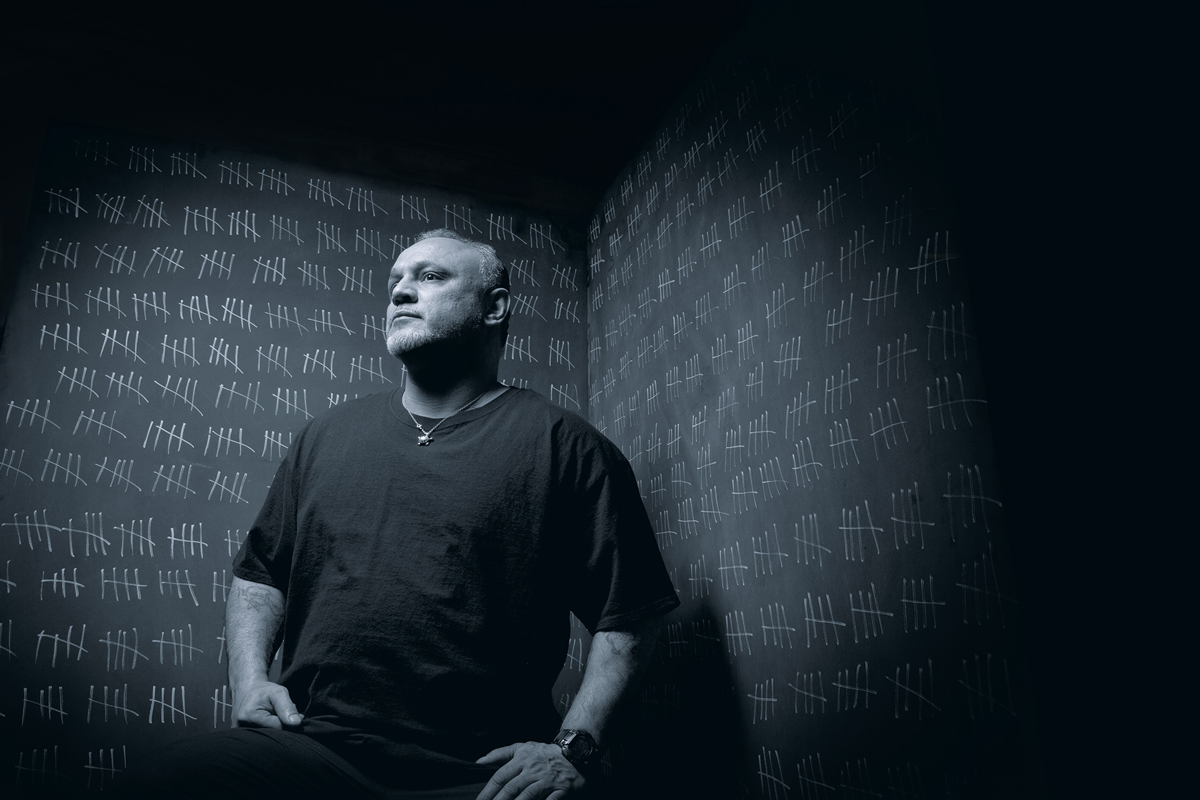

The stories and themes of the film are further brought to life as each exoneree sits in a corner surrounded by the stark, black backdrop. “I wanted to get this feeling of loneliness across ... Just a powerful kind of portrait that might just draw people in to hear what they have to say,” Goodwin says. “I wanted something consistent that I could have for all six of the people, so that's why we built this background and had everyone wearing black t-shirts. I wanted to hear from them and to not be distracted by anything.”

To an outsider it might not be apparent but “Exonerated,” is Goodwin’s first professional foray into video. “You can tell that it probably is somebody's first effort because technically speaking, it's got it's flaws for sure,” he says. “These are our Canon Mark IIs and Mark IIIs that we're using on this, and just a couple of LED lights and the sound is not great. We're just a three-man crew. It was pretty minimal.”

Despite the learning curve that comes from developing any new skill, Goodwin found that he enjoyed working in the film medium. “I loved doing it. I'm pretty good at producing and figuring out what needs to happen and what we need to capture. I came up with the ten or so questions to ask everybody so there was consistency, but ultimately I knew it was going to need to land in the lap of a really good editor who could put the story together.” he says.

After a referral from Craig Duncan at Cutter's Studios, Goodwin found the editor he needed in Patrick Duffy at Cutter's Detroit offices. “Patrick really took it to the next level with editing in the news footage. He came up with the idea of a little special effect with the hash marks being checked off as you're watching and the music and the pacing in general. I was really impressed with what he was doing with it. As a still photographer, I'm used to overseeing a lot more of the project, and this to me was a lot more of a collaboration in terms of needing good post work, somebody working the sound, and all of that kind of stuff.”

Leroy Orange served 19 years on death row for a crime he did not commit. “There was no apology and I don’t think there ever will be.”

The collaboration continued as the two went back and forth over the raw material. “If I sat down with this stuff, I would have done all of Kristine Bunch's story first, then I would have done Juan Rivera's story. The way that Patrick jumps around and moves back and forth maybe on the same question, I just thought, ‘You know this is the way to do it.’ Anybody can go buy video software, but to really put it in the hands of somebody that's good at this kind of thing made all of the difference.”

When “Exonerated” was finished, Goodwin presented it to the Center’s Sara Sommervold. The Center was thrilled with the result. “They have been able to use it on their site along with the portraits I took. They do fundraisers now and they've blown up these pictures to 5 ft. x 3 ft. and they are using the heck out of this stuff, so they are really digging it. The exonerees do too. They've been all so excited to have some awareness about their stories. I stay in touch with a few of them and we’re talking about continuing on with this project and shooting more video.”

When Goodwin and his team entered “Exonerated” in the Midwest Independent Film Festival, they were pleasantly surprised when they got a call back about their work. “[They said,] ‘Hey, we've got it narrowed down to 50 or so and we think we'd like to include you. We need a little bit more information...’ Then it came down to the final 18 and we were told that we had made that cut as well. We were all so excited you know? I bought a bunch of tickets and brought a couple of the exonerees with me that night, Juan Rivera and Jacques Rivera and Patrick Duffy came in from Detroit. I had no idea they were going to narrow it to three and then a “best of show” kind of thing.”

Jacques Rivera served 21 years of an 85 year sentence for a crime he did not commit. "I missed being a father to my kids. I had to leave them on the streets of Chicago."

When the final eight films were announced Goodwin and Duffy joined the other directors on stage. “Patrick came up with me and they announced the top three and then they said, ‘And the first place goes to “Exonerated.’" The place just went wild it was just like, I couldn't believe it...I invited Jacques and Juan to come down to the stage and they were treated like celebrities that night at the after party. It was an amazing night for sure.”

Following the success of “Exonerated,” Goodwin says he’d like to work more pro bono projects into his schedule. “I haven't seen any direct response, but I do have some other pro bono projects coming up with some agencies that I've wanted to work with and this may end up being a foot in the door,” he says, noting a recent project with the Make-a-Wish Foundation, and an upcoming shoot with a homeless campaign. “I find now that at this point in my career, I really like the idea of not just strictly being about the money and just taking on whatever project comes in. I'm trying to split it up a little bit, not just the awesome commercial projects I've been fortunate enough to work on but I'd also love to regularly work on these pro bono projects and help out and do that kind of good work.” He’s also started to do fine art photography and has his Charreada series being represented by the Catherine Edelman Gallery.

As to whether “Exonerated” has inspired him to use Facebook and other social media platforms more regularly, he says, “I can point to a project or two that definitely came in through stuff I'd posted on Facebook. It's a great way to get the word out there and sharing new work, keep letting people know what you're up to.”

But despite the added value of social media to his business, at the end of the day, there’s nothing like connecting with peers, clients, and collaborators on a more personal-basis, including through industry groups like APA. “As creative people, a lot of us are pretty like-minded when it comes to social and political causes. It's great to get together with peers and discuss and talk about what we can do to make positive change and I look forward to spending more time with some of the APA folks.”